Matilda Allison was born in Illinois in 1843, as one of eight children to a farming family. She was trained as a teacher and taught for many years in Indiana County, Pennsylvania, until she was commissioned by the Women’s Board to come to Santa Fe. She is thought to have previously stopped in Santa Fe en route to Chihuahua, Mexico, as a First Presbyterian Mission through New Mexico.

At the time, becoming a missionary teacher was one of the few options for an independent, single woman. Women, like Allison, who wanted to effect social change could do so from the traditional roles of education and church involvement. These female missionaries were part of a broader trend of women’s groups expanding influence in the Church.

“The word Presbyterian stands for education among the Mexicans.”

In May of 1881, at the age of thirty- eight, Allison arrived in Santa Fe from Marchand, Pennsylvania, where she was greeted by Rev McGaughey. Within her first few weeks, she reinvigorated an existing mission school that had become neglected over time. Allison’s goal as a missionary teach was to provide an adequate education in a place with few schools and beat back the Catholic influences. Families were encouraged to pay the school in goods, but as the Santa Fe New Mexican reported, “There will be no charge for tuition and books will be furnished for those who cannot purchase them. At the request of the city a separate room will be provided for pay pupils for a period of two months…The tuition will be $2.00 per month.” There were, at first, 23 pupils including “seven Spanish-speaking, six colored, and ten white.” After Allison’s arrival, the brick church was erected.

In May of 1881, at the age of thirty- eight, Allison arrived in Santa Fe from Marchand, Pennsylvania, where she was greeted by Rev McGaughey. Within her first few weeks, she reinvigorated an existing mission school that had become neglected over time. Allison’s goal as a missionary teach was to provide an adequate education in a place with few schools and beat back the Catholic influences. Families were encouraged to pay the school in goods, but as the Santa Fe New Mexican reported, “There will be no charge for tuition and books will be furnished for those who cannot purchase them. At the request of the city a separate room will be provided for pay pupils for a period of two months…The tuition will be $2.00 per month.” There were, at first, 23 pupils including “seven Spanish-speaking, six colored, and ten white.” After Allison’s arrival, the brick church was erected.

Matilda Allison could not have come to Santa Fe without the help of the Presbyterian Ladies’ Board of Missions of New York. These ladies had been deeded the real estate of the school building and were in charge of funding a chosen teacher for the school. These ladies commissioned Allison to go to Santa Fe, just as other groups of women were beginning to fundraise for other missionary teachers across the west. As the Presbyterian Church shifted towards education-based western missions, local mission boards formed to find and fund female teachers to serve as missionaries, as these missions were considered the most appropriate for female sympathies.

In 1884, the school began taking a limited number of girls as boarding students. As Matilda Allison stated, her objectives were to “surround [the girls] with Christian influences, teach them how to live, teach them the truths of the Gospel and to have the Word of God so permeate their hearts and minds that it should mold and control their future lives.” These girls were trained in domestic work, as well as academic subjects, and Allison’s curriculum soon became a model for the public schools. As stated by the Santa Fe New Mexican, “Graduates of the institution are much sought after by families desiring competent help.” The adobe church was used to house these girls.

Asked: “Does it pay to keep these girls in school?”

Answer: “My life would not have been worth living if I had not given it to this mission school work.”

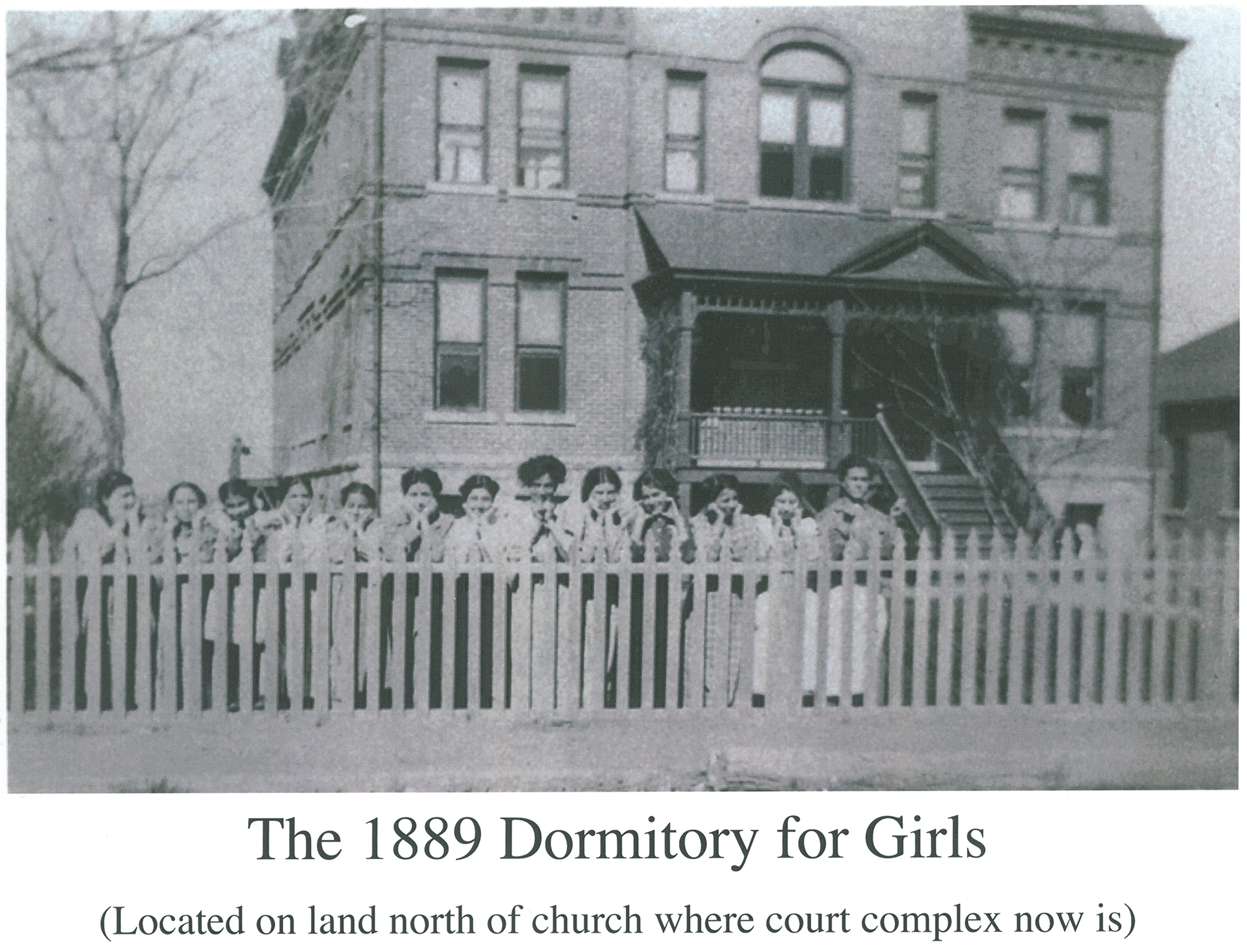

As the school held in the adobe building became a pile of crumbling mud walls, Allison started looking to expand. In October 1889, a three story red brick dormitory and classrooms came into use. At this point in time, there were seventy- four girls enrolled. During this time of transition, the school became the Presbyterian Boarding and Industrial School for Girls under Woman’s Board of Home Missions.

As the school held in the adobe building became a pile of crumbling mud walls, Allison started looking to expand. In October 1889, a three story red brick dormitory and classrooms came into use. At this point in time, there were seventy- four girls enrolled. During this time of transition, the school became the Presbyterian Boarding and Industrial School for Girls under Woman’s Board of Home Missions.

Though the school was beginning to prosper, tragedy hit. In 1891, a diphtheria epidemic tore through Santa Fe, striking the school in April. Two students died (who are buried in Fairview Cemetery) and the rest were evacuated to avoid the disease, and the last student left that June.

As the school grew, Allison fought for the right to educate girls. While her curriculum was not particularly revolutionary and centered on vocational skills such as sewing and cooking, several of her students’ parents “could not understand our interest in [their daughters].” While girls in the east, where Allison grew up, were expected to know how to do sums and read as well as have domestic skills, western girls often did not complete their educations because they married early. Furthermore, Allison found herself fighting against a culture that was just coming to terms with the increasing educational opportunities, as families were reluctantly beginning to send their children to new schools.

In 1900, the school was continuing to grow, despite facing the challenges from disease and cultural misunderstandings. By 1901, other buildings including a four-room classroom building, a laundry, a teacherage, and student living rooms were added.

As Allison’s school continued to expand, so did her position in the Presbyterian community. After years of trying to start an institute to yearly help teachers increase their skills, Allison took over. In August 1902, she led a Teacher’s Institute for Presbyterian educators in near-by areas. These teachers had Bible lessons, devotionals, and discussions on topics relating to the mission of New Mexican schools. As a result, those in attendance created a plea to increase the school facilities in an effort to reach more students.

In 1903, Matilda Allison retired at 60 years of age, after 22 years of service, due to ill health. In order to recuperate, she moved to sunny southern California. During the time Allison served Santa Fe, First Presbyterian had seven pastors (McGaughey, Stark, Jones, Ferguson, Smith, Craig, and Moore). As a tribute to her years of service, a time of her retirement, Rev. Hayes Moore wrote a resolution to change the name of the school, and in conjunction with the Session of First Presbyterian Church, it became named the school “The Allison School.”

After her health returned, Allison moved back to New Mexico in 1906 to help build a new church and teacher’s house in Truchas. She was instrumental in finding funding through her friend George G. Smith (who was pastor at First Presbyterian Church, Santa Fe, from December 1887 to April 1895), with whom she had worked in Santa Fe. Rev. Smith had received a large inheritance, and she suggested to him that he might like to give it for the mission. He was happy to do it. Miss Allison suggested the building be named the George G. Smith Memorial Presbyterian Church in Truchas.

Three years later, in 1910, Allison retired for good to Los Angeles, California. Even in her retirement, she remained committed to the cause of missionaries in New Mexico. On August 15, 1913, after delivering a missionary address about her past activities in New Mexico, she collapsed.

Return to History Overview